Flux

Change is Everywhere

Why you should actively seek change

The philosopher Heraclitus famously said the only thing constant is change. Not only is change omnipresent, it is happening faster and with more intensity than ever - which is why you should actively seek change yourself.

You might be wondering, if the world is changing so fast, why do I should go out of my way to seek it? Won’t change just come to me? Yes. And that’s exactly the problem. When change comes, it often brings with it discomfort, displacement, and disruption especially to those who are unprepared to handle it. To those who are prepared, change can be a powerful catalyst for growth, opportunity, and construction. But to prepare, you have to learn the how to handle change.

Handling change is a skill

Like all skills, handling change requires exposure. How experienced you are at handling change is dependent on how much exposure to shocks you’ve had.

I once worked at firm during a time when it was hemorrhaging money. Management decided to make cuts up and down the employee ladder. Both senior and junior employees were let go. For nearly all, it was the first major negative employment shock they experienced. It was an extremely unpleasant time, filled with fear and anger.

The clear experience gap that existed between the senior and junior employees during stable office times evaporated when exposed to sudden unemployment. The senior employees had the same shock as the junior employees. You would think that those with their “10 years of experience” would have an edge compared to the junior ones who had essentially just graduated college. But they didn’t; they were just as lost as their junior counterparts. When the shock came, they were just as “experienced” as a young green college graduate.

Positive and negative change

We like to categorize things as positive or negative. A binary classification is a very practical way to simplify a complex world. When we run into a bear on a hike, we do not question whether the bear means us harm or is simply traveling across the forest to find berries. That would be extremely impractical. Rather, we quickly classify the bear as capable of doing harm (i.e. negative) and decide to get out of its path. The person who chooses to analyze the bear for too long may not exist much longer. While useful in such practical situations, this approach can be rather flawed when analyzing our own reaction to change.

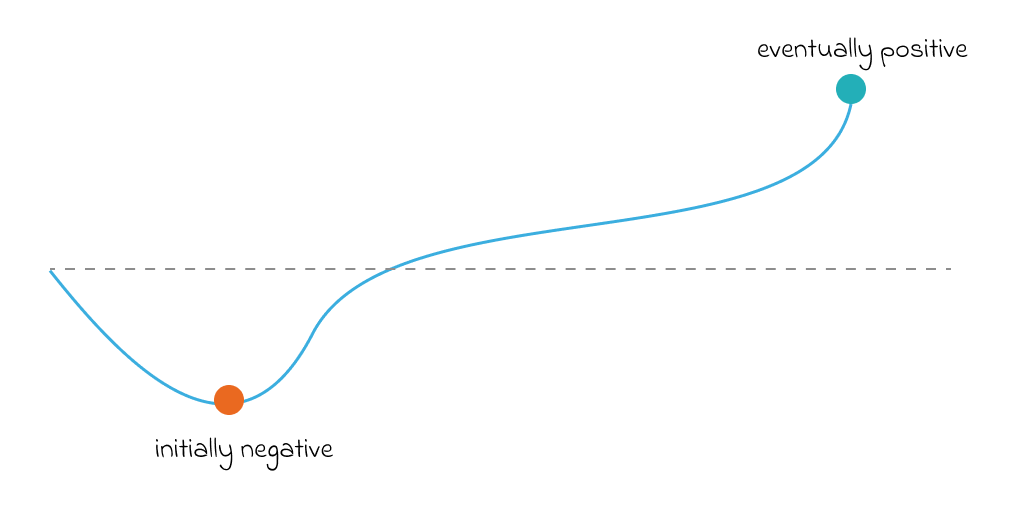

Immediately after the layoffs, nearly everyone viewed the event as, understandably, extremely negative. But years later, most viewed the event in a primarily positive light. None of them had particularly enjoyed the job, and the shock proved to be a forcing function to change to something they enjoyed more. While the journey was painful, it led them to a better place. So was the change positive or negative?

Change is inherently uncomfortable and risky. Like with the bear, we have a tendency to take a quick reading based on the immediate situation and classify it accordingly. But as we have seen, people can modify their classification over time. This is because the consequences of those events are not fully played out. And it is the actual consequences of change that ultimately define it as positive or negative.

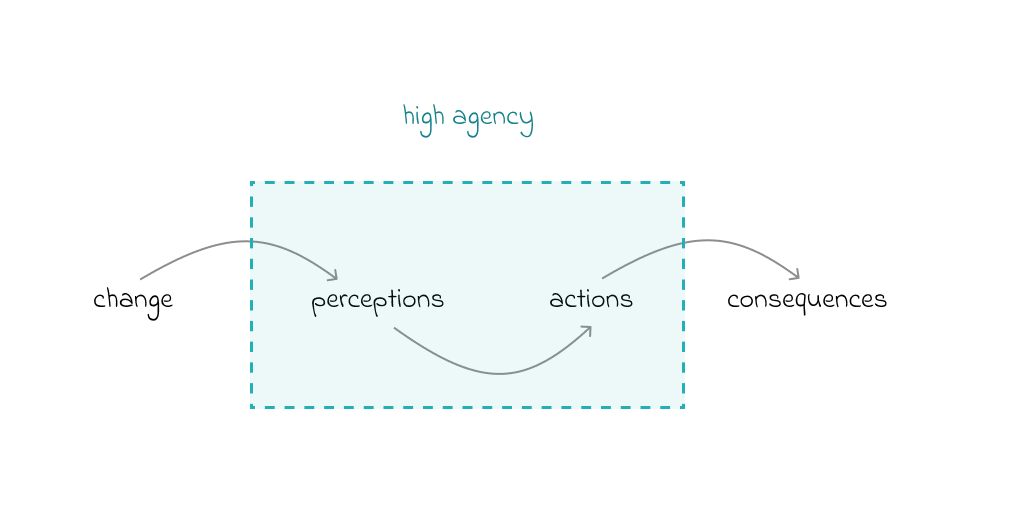

Focus on agency

Let’s back up. If consequences define positive or negative change, then what impacts consequences? Our actions. And how do we choose what actions to take? By our perceptions. The chain of events starts with an input (change). How you perceive the change then impacts what actions you take. What actions you take in turn impact what consequences you end up with.

In this chain, you have little to no control over the input itself and can you never fully control the output. It is your perceptions and actions that you have the most agency over. This makes them the most useful areas to focus on to maximize the chances of a positive outcome. This doesn’t mean that you can completely define how change will impact you, but it does mean you have more of a hand in its future formation than you might think.

Learning Through Exposure

Actions create change

Learning change requires exposure to change. Just as you can’t learn tennis from reading about it, you can’t learn how to handle change if you don’t actually experience it yourself. So how do you get exposure to change?

For the intellectually minded, it’s generally more preferable to learn by finding the knowledge you want and then reading about it. Reading may imbue you with knowledge, but you have to put the knowledge to use for anything to happen. Reading is a complementary aide - not a substitute for action itself.

Reaching difficulty

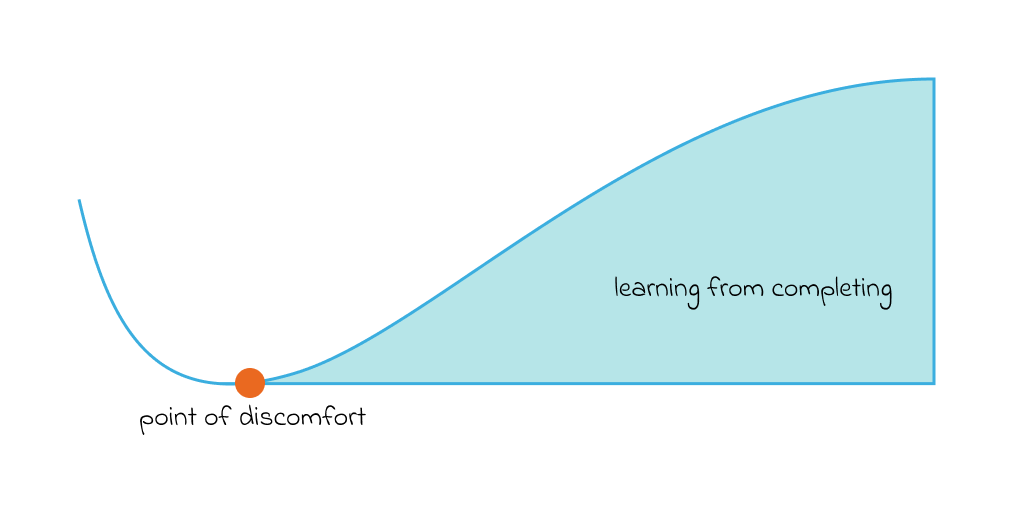

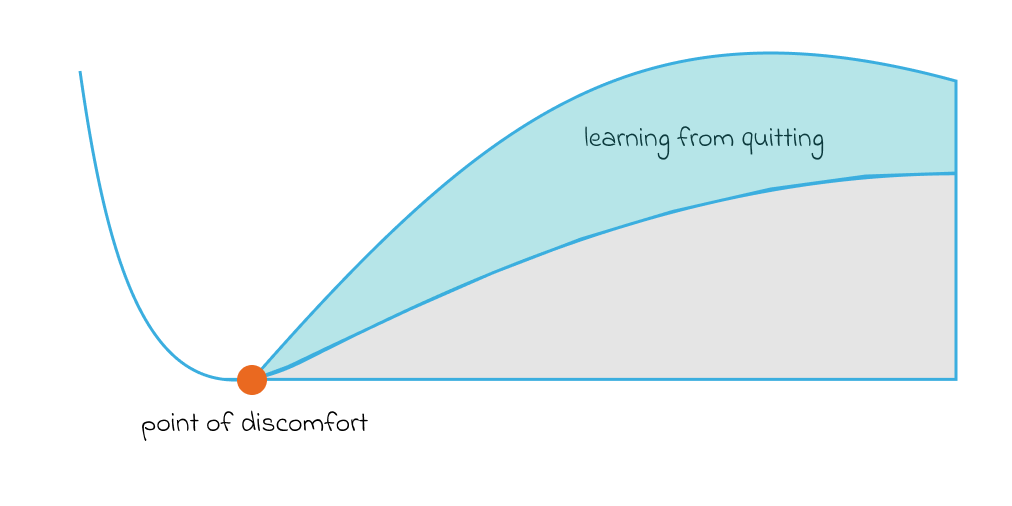

There are usually two main times where you learn something important during an action:

- when you force yourself to complete it

- when you quit

Completing an action can give you a new perspective on change. Most actions will follow a curve of being exciting to start, followed by a descent into “why am I doing this again?” territory. While unpleasant, this low point is where all the learning starts. If you can convince yourself to keep going even when it’s unpleasant, then you gain a little exposure in handling the initial discomfort that comes from change. Your mental fortitude increases a little.

The next place you learn something is when you quit. Again, the low point is the key as most quitting is going to happen when things get unpleasant. Contrary to perhaps most conventional advice out there, quitting can be very useful because it can reveal a false desire. If you think you want to create a newsletter, but you find the constant need to produce content to be exhausting, you might not really want to create a newsletter. Perhaps what you really enjoy is discussing a topic in-depth and you would be happier with a more engaged community and publishing intermittently. In this situation, quitting is actually to your benefit because it frees you up from chasing something you don’t really want and gives you back the opportunity to try new approaches.

Which point to aim for

If you can learn both by completing and by quitting, then which one should you aim for? If you gain upside from both scenarios, then aiming does not really matter. What matters is reaching the low point so that you can find yourself in a situation where you can learn something. If you preemptively quit before hitting the low point, then you don’t discover anything. Did you quit because you weren’t interested? Were you just too busy? Were you not disciplined enough? It’s hard to say because you never hit the key stressor of difficulty. So instead of focusing on either completing or quitting, focus on getting to the point of difficulty. And then go a little further. From here, whichever direction you go, you’ll likely learn something.

Diversifying environments

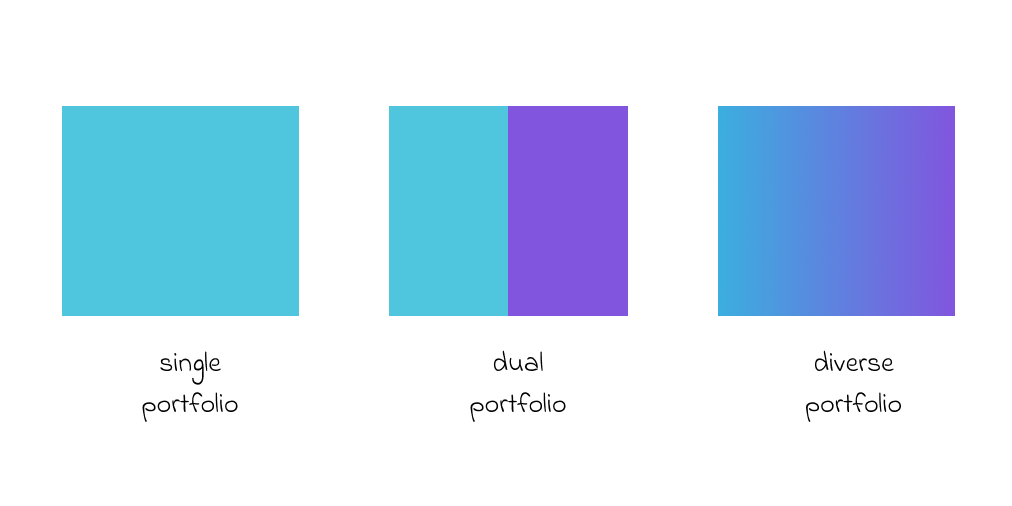

The other way to gain exposure to change is to selectively diversify what environments you’re exposed to. Environments are extremely useful to learning how to handle change because they force you to respond. Imagine moving to a new city where you know no one. This new environment would force you to behave differently than you would were you living in your hometown surrounded by people you know.

Environments can be soft or harsh and choosing which ones you should experience requires moderation. If you only operate in extremely harsh environments, you are liable to break or become extremely jaded. The point isn’t to hurt yourself, but rather to learn how to handle change better. By the same token, if you only stay in soft environments, it will be very hard to acquire the fortitude you might need when change comes your way. One might wonder, if change is hard why wouldn’t I just stay in harsh environments to learn? What is the value of a soft environment, besides that it would be more comfortable?

Just because you can thrive in a harsh environment, doesn’t mean you can thrive in a soft one.

That’s a little bit like saying if you can be mean, then you can be kind. Change is hard because it is different from what you are used to. If you are used to harsh environments, then a soft one will be difficult for you.

It’s true that if you are more exposed to hardship, you are generally going to have more tools to survive than someone who hasn’t. In your portfolio of environments, having a greater allocation for harsher environments is probably beneficial. But exclusively focusing on harsh environments is most certainly not. This is because the kind of tools you gain from harsh environments cannot be used in soft environments as is. The usefulness of a tool is entirely dependent on the environment in which you operate in.

Imagine a very aggressive street dog - one who has fought and won many battles to survive. Then a person takes him in and he has to learn to be a civilized pet. The skills he has learned - how to fight, how to steal, how to hunt - are not useful anymore. In fact, they are actively detrimental. If the dog bites another dog or hurts another human being, the owner will have little choice but to put him down. What was useful in one environment became harmful in another.

Harsh and soft are simplifications. In reality, environments exist across a wide spectrum. It pays to build out a diverse portfolio of environments to experience. It increases the chances that you’ll have a decent working model to go off when change strikes.

Getting Over Failure

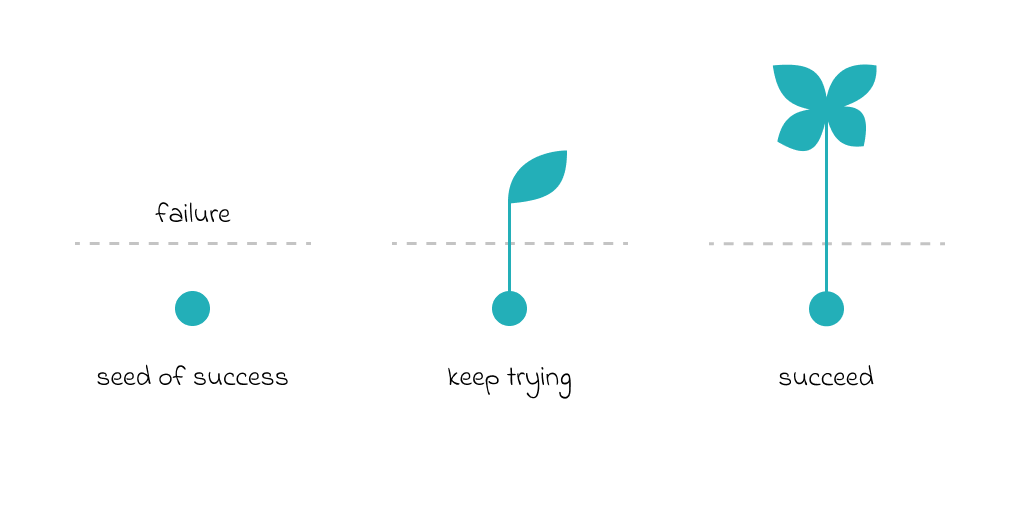

Failure is the start

All growth starts first from failure. This may sound negative, but it’s not. It means that if you fail, you have the capacity to grow by default. The only thing that has zero capacity for growth is something that is perfect. The difficulty arises in the fact that while failure is the starting ingredient of growth, it is also an extremely undesirable state to be in. Everyone wants to grow, but no one wants to experience failure.

Who defines failure?

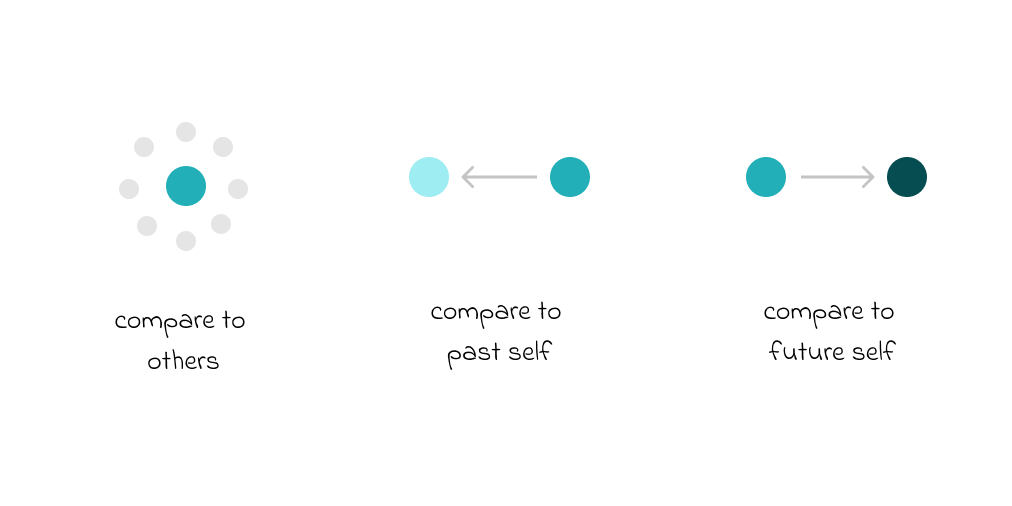

Failure is referentially defined - that is in comparison to something else. If failure is referentially defined, then there is no standard definition. It is entirely dependent on the frame of reference chosen. There are three common frames of reference:

- You compare yourself to others - this approach makes you externally focused and is the easiest to measure

- You compare yourself to your past self - this approach makes you focus on progress, as progress is equated to success

- You compare yourself to your future self - this approach makes you internally focused but it’s hard to measure

No frame of reference is superior to any other. Each has its own merits and flaws. The value is in the ability to switch your frame of reference when you need to. Switching frames

The biggest problem with failure is that it discourages you from trying. The only people who speak openly about their failures are those who have managed to turn them into successes. There is a tolerance for how much failure we can sustain about ourselves before we became discouraged. The ambiguous state of not trying is preferable to the state of confirmed failure.

For this reason, I advocate being flexible with the frame of reference and to pick the one that is the most likely to encourage you to keep trying. If you compare yourself it to your future self and you feel that you have failed, then it may be to your benefit to actually turn externally and compare against others. Likewise, if you have always compared yourself to others and feel that you have failed, it may be beneficial to turn inward and seek a comparison against your past self.

In this approach, I am not overly concerned with what is the “truth” but rather what is useful. If failure is referentially defined, then all things are true so it’s not a very helpful approach. Truth is only meaningful for such matters if it also illuminates what is false so that you can pick the right path and ignore the wrong one. But if all things are true, then you’re again at an impasse. The alternative is to focus on what is useful. In the proverbial question of “is the glass half-full or half-empty?”, both statements are true but only one is useful.

Seed of success

A big part of recovering from failure is finding something you are proud of during the process of failing. Pride is a crucial because failure is ego death. Too much of it and it becomes detrimental to your confidence. And you need confidence in order to try again.

The something you find to be proud of can be small, but it is almost always built on character rather than results. If you really wanted to win the championship, telling yourself that at least you placed is not very effective consolation. Telling yourself that you put in showed impressive work ethic and played bravely is significantly more effective. You can take pride in the fact that you have proven you are capable of working hard and being brave no matter what the result was. It is a seed you can grow into a future success.

Managing Progress

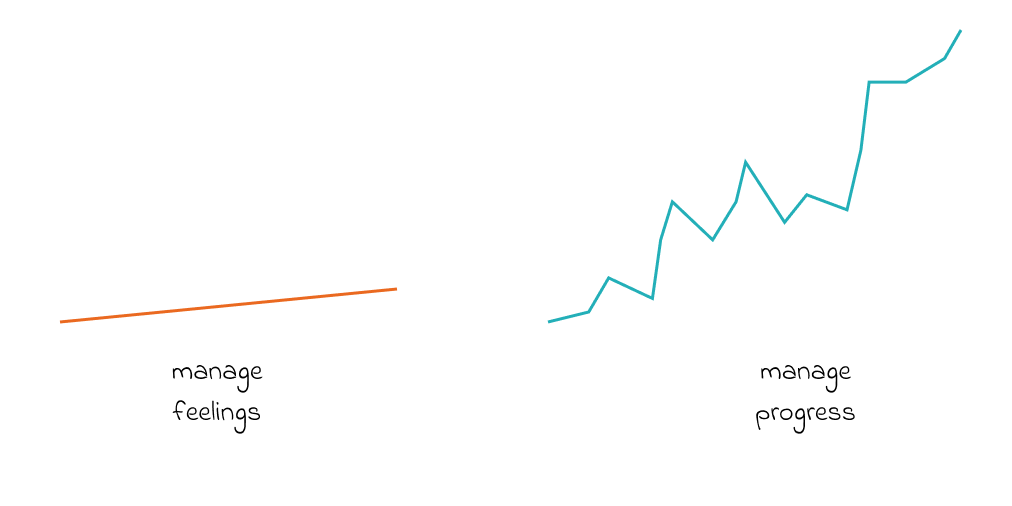

Feeling vs. actuality

The feeling of constant progress is addicting. Unfortunately, if you always feel like you’re progressing, you probably aren’t. This isn’t to be confused with the phenomenon of actually growing. If you’re actually growing, chances are you will feel up and down all the time. Sometimes you’ll feel intense growth and other times you’ll feel like you’ve been here before and nothing’s changed. The variation in feelings is a leading indicator that you’re actually experiencing growth.

When you always feel like you’re making progress, chances are you’re in your comfort zone. And the growth that comes from comfort gets tapped out quickly. A trainer that makes sure you feel great for each session is not as effective as one that pushes you stretch and perform outside your comfort zone. One will make you feel better, the other will actually make you better.

Forward neutral

After a few times of teaching preparation programs, I noticed a marked difference between students based on their attachment to progress. Forward only students were students who insisted that with each session they should feel they are moving forward. Forward neutral students were students who didn’t have this expectation and generally understood that sometimes you’ll feel like you’re going backward. They didn’t like it, but they accepted it as part of the process.

When it came time to perform, forward only students were extremely confident and shot out of the gate while forward neutral students were well, neutral, or in some cases moderately negative. But as results started trickling in, confidence levels for forward only students started to plummet. Some of them landed, but the majority broke at the first sign of going backward, having never really learned to deal with it before. Forward neutral students started out slow, hit a few roadblocks, adjusted accordingly, and proceeded to continue until they landed.

Overall, the results for forward neutral students were significantly more consistent than forward only ones. Forward neutral students had learned how to be resilient in exchange for the feeling of seemingly perpetual confidence and progress. Forward only students had taken the opposite trade.

Speed of recovery

No matter how well-practiced you might be or how many changes you’ve gone through, change will always be uncomfortable. More exposure doesn’t mean that change will become comfortable and easy. Even with hundreds of repetitions, change will still be uncomfortable every time.

You can determine if you’re making progress by assessing how fast you recover from change. The better you get at handling change, the faster you’ll recover. Don’t be discouraged if you feel uncomfortable when change happens. Instead, assess how long it took you to go from feeling discomfort to feeling neutral about the change. How fast you’re able to do that is a sign of how well you are handling change.